The Congressional Budget Office has released an analysis of the new House Republican tax plan which indicates that the deficit will increase by $1.7 trillion over the next decade. Obviously, that is not a good thing but how big a deal is it? Here are some numbers that provide some perspective on that question.

The most widely used (and I think most meaningful) measure of government debt burden is the ratio of a nation’s net debt to its annual Gross Domestic Product. It’s the basically the same concept a credit agency might look at the balance sheet of a family or a business. $50,000 in debt is very troubling for household with $25,000 in yearly income. But a household with $500,000 in yearly income could quite easily assume more debt if necessary.

Obviously, the lower the debt as a percentage of GDP the better. A country with a low debt to GDP ratio can borrow a lot of money if it finds itself facing external military threats, natural disasters or the kind of economic calamity that hit the U.S. in 2008. During World War II the U.S. ran its public debt to about 110 percent of GDP but quickly put itself back on the path to fiscal strength after the war—cutting its debt ratio to under 25 percent in only 28 years.

When the European Union decided to create a common currency, they picked a debt to GDP ratio of 60 percent as the appropriate target for member countries. Clearly countries below the 50 percent level are in relatively strong positions to confront whatever problems their citizens may face.

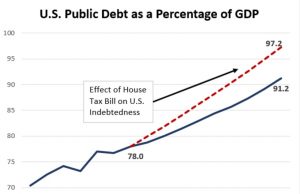

So, the question is what does the $1.7 trillion in additional public debt that the CBO forecasts will result from the House tax bill do to this measure of fiscal health?

Today, U.S. debt as a percentage of GDP has climbed to 78 percent—an already precarious level. Worse still CBO projects that under current tax law and spending policies it will continue to climb at an average rate of 1.75 percent per year over the next decade. This is despite sharp (and I believe unrealistic) cuts assumed by CBO in spending for the daily operations of government ranging from law enforcement to veteran’s care and investment in science, education and transportation.

Baby Boomers like me are retiring in droves and their Social Security and Medicare benefits will push the spending side of the federal budget from 21 percent of GDP to more than 22 percent even as spending on the rest of the budget is assumed to decline.

By 2027, CBO projects that the federal debt will equal 91 percent of GDP. But adding another $1.7 trillion to that debt by 2027, the Republican Tax plan will increase the pace at which debt is rising as a share of GDP from 1.75 percent a year to almost 2.5 percent a year. That would put debt at more than 97 percent of GDP by the end of the period and well above 100 percent by 2030.

That is not only grossly irresponsible it is destabilizing. Such growth in the debt/GDP ratio is certain to force corrective measures. Either new taxes will have to be imposed or spending will have to be cut or both.

So the question that people should be asking about this tax bill is not simply whose taxes go up based on the language in this specific piece of legislation but whose taxes will be forced up in the future and whose retirement benefits or programmatic needs ranging from education to national security will be slashed to sustain the revenue giveaways defined in this bill?

The legislation threatens the future of a great many people who at present remain unaware of the danger.